Iceland is proud of its people and its culture, and works hard to preserve its heritage in both language and the arts. While the country is physically isolated, Icelanders welcome visitors and immigrants. The capital city, Reykjavík, is in particular known as an international city.

Population

Roughly 400,000 people call Iceland home, and more than two-thirds live in the capital city, Reykjavík, and its suburbs. Outside Reykjavík, Hafnarfjörður, and Kópavogur, the most populated towns in Iceland include Keflavík and Selfoss in the south, Akureyri in the north, Akranes and Borgarnes in the west, and Höfn and Egilsstaðir in the east. About 85 percent of the island’s population are native Icelanders, but the foreign-born population continues to grow with the inflow of migrant workers, asylum seekers, and refugees.

Native Icelanders have a genetic makeup that combines Celtic and Norse heritage, and many Icelanders consider themselves Nordic rather than Scandinavian. Social lives center on family, as Icelanders tend to be a close-knit bunch. It often seems like all Icelandic people either know one another or have friends in common.

Language

The official language of Iceland is Icelandic, which is considered a Germanic language. Icelanders like to think of their language as poetic and musical, and maintaining their tongue is an important part of Icelandic culture. Most Icelanders speak English and are happy to converse with visitors in English, but they enjoy when foreigners give the language a try, even just a few words. The closest language to Icelandic is Faroese, which roughly 50,000 people speak, and the other close language spoken by a larger group is Norwegian. Many Icelanders can understand Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish due to the similarities. Learning Icelandic is a challenge for many foreigners because of the complex grammar and accent.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Icelandic Names

Iceland has a strident naming committee that must approve names parents wish to give their newborns, in the spirit of maintaining Icelandic culture. For that reason, you will find a lot of common first names, including Bjorn, Jón, Ólafur, Guðmundur, and Magnús for males, and Guðrun, Sara, and Anna for females. Very few Icelanders have surnames; instead, Iceland follows a patronymic system in which children are given their father’s first name followed by -son or -dottir. If a man named Einar has a son named Johannes and a daughter named Anna, their names will be Johannes Einarsson and Anna Einarsdottir.

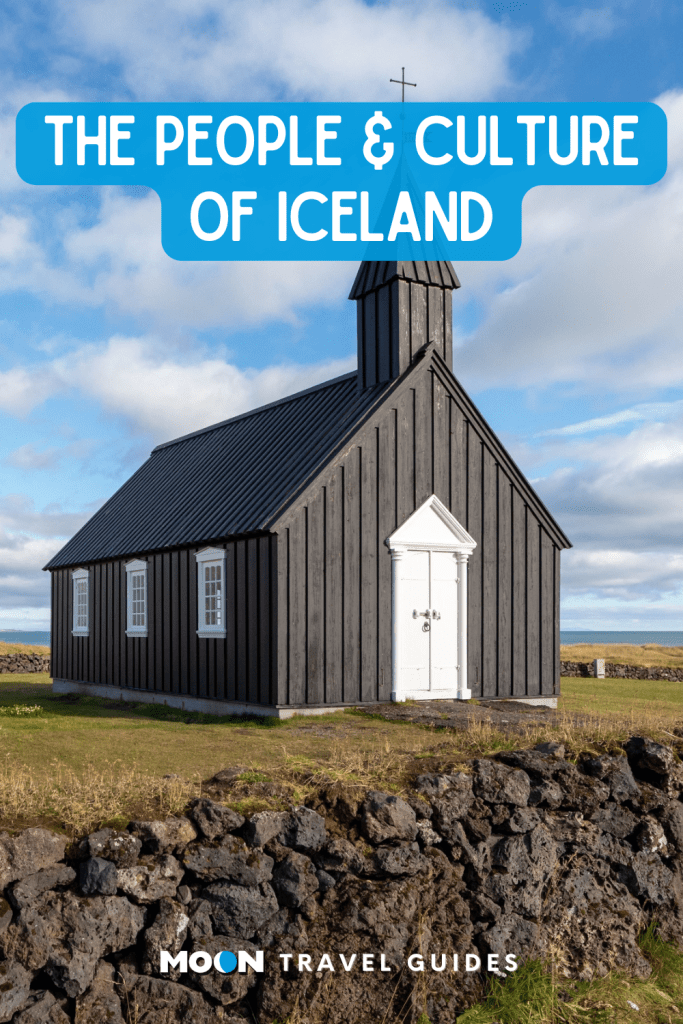

Religion

Icelanders have an interesting relationship with religion. Most of the country, about 60 percent, identifies as Lutheran, but most Icelanders aren’t known to attend church regularly or be very vocal about their religious beliefs. While the majority of the country identifies as Christian, Iceland is considered a progressive nation. There is no separation of church and state in Iceland; the National Church of Iceland is subsidized by Icelanders through a church tax. However, the nonreligious can choose to have their church tax donated to designated charities.

Of Iceland’s religious minorities, Roman Catholics are the largest group at about 4 percent, and there are an estimated 3,000 Muslims that call Iceland home, as well as about 300 Jews. There is not a single synagogue in Iceland, as the Jewish population has not requested one, but a rabbi relocated from New York to Reykjavík with his wife and children in 2018. A mosque was approved by Reykjavík in 2014, and construction is ongoing as of 2024. The pagan Norse religion Ásatrúarfélagið has grown in membership in recent years to about 5,000 adherents.

Arts

Music

Music plays an important role in Icelandic society. There’s an emphasis on children learning to play instruments, with music schools around the country. It seems that everyone in Iceland is in at least one band. The earliest Icelandic music is called rímur, which is a sort of chanting style of singing that can include lyrics ranging from religious themes to descriptions of nature. Choirs are also very common in Iceland, and there are frequent performances in schools and churches that are usually well attended by the community.

As for modern music, Iceland boasts quite a few bands that have gained a following abroad. Of course, there’s Björk, who put Iceland on the musical map back in the 1980s

with her band The Sugarcubes and later her solo career. Icelanders tend to be quite proud of Björk as both an artist and an environmentalist. Sigur Rós, who have been recording since 1994, have become an indie favorite. Laufey, Of Monsters and Men, Kaleo, Ólafur Arnalds, Amiina, and GusGus are taking the world by storm. Reykjavík has cool venues in which to check out local bands and DJs, and some great record shops to pick up the newest and latest Icelandic releases.

Literature

Iceland has a rich literary history. The sagas, considered the best-known examples of Icelandic literature, are stories in prose describing events that took place in Iceland in the 10th-11th centuries, during the so-called Saga Age. Focused on history, especially genealogical and family history, the sagas reflect the conflicts that arose within the societies of the second and third generations of Icelandic settlers. The authors of the sagas are unknown; Egil’s Saga is believed to have been written by Snorri Sturluson, a 13th-century descendant of the saga’s hero, but this remains uncertain. Widely read in school, the sagas are celebrated as an important part of Iceland’s history.

The nation’s most celebrated author is Halldór Laxness, who won a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1951 for his cherished novel Independent People. His tales have been translated into several languages and center on themes near and dear to Icelanders—nature, love, travel, and adventure. Other authors who have been translated into English and other languages include Sjón, Arnaldur Indriðason, and Einar Már Guðmundsson.

Knitting

Icelanders have been knitting for centuries, and it remains a common hobby today. Wool from Icelandic sheep has been keeping Icelanders warm for generations, and a traditional modern sweater design emerged in the 1950s or so in the form of the lopapeysa. A lopapeysa has a distinctive yoke design around the neck opening, and the sweater comes in a variety of colors, with the most common being brown, gray, black, and off-white. Icelanders knit with lopi yarn, which contains both hairs and fleece of Icelandic sheep. The yarn is not spun, making it more difficult to work with than spun yarn, but the texture and insulation are unmistakable.

Plan your trip:

Breathtaking landscapes, unrivaled trekking, and the creative spirit of Reykjavík: experience it all with Moon Iceland.

Build your Europe travel bucket list

Get inspired and get ready for adventure with the ultimate guide to Europe’s best trips!

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Pin It for Later